Good morning, Aston Martin Aramco fans. This is your Captain speaking. Welcome to your special training detachment. You all know Formula One, but just how much do you really know about the science of what a driver is subjected to in the cockpit?

This training will teach you how the human body deals with the incredible physical demands of driving an F1 car as we invite you to See the Science of the sport – and reveal why Lance Stroll and Fernando Alonso are more 'Top Gun' than you could ever imagine.

Your instructors? Aston Martin Aramco Team Doctor Rahul Chotai, call sign: Doc, and Team Ambassador and former F1 driver Pedro de la Rosa, call sign: Bullet – short for the 'Barcelona Bullet' moniker bestowed upon him for his raw speed and consistency under pressure.

Let's turn and burn...

150 beats per minute – and climbing. Take my breath away.

During a Grand Prix, F1 drivers sustain heart rates of 150–190bpm. Fighter pilots see spikes of 160bpm during high g-force manoeuvres and combat. Both endure cardiovascular strain, but drivers maintain extreme rates continuously while pilots experience short, intense bursts.

DOC: "A driver's heart rate stays near marathon levels for two hours."

BULLET: "Yeah, over a normal race distance, your heart rate is around 170bpm. It can lower slightly on straights before rising again through corners.

"It's even common for a driver's heart rate to reach more than 180bpm in the opening seconds of a Grand Prix. I once hit 204bpm in a Formula 3 race.

"Once the lights go out, you select first gear and instinct takes over. You don't think, you act automatically. You've visualised the start before; waiting for the fifth light to go out, putting the revs in the right window, but when the race starts for real, you are on autopilot. You're not conscious of what you're doing; it feels like you don't even breathe for the first 30 seconds."

DOC: "What Pedro's describing is because, at lights out, the driver's body goes into a 'fight-or-flight' mode.

"Adrenaline surges, boosting heart rate, breathing, and blood flow to muscles. Breathing becomes shallow in the first moments of the start due to chest pressure, but controlled techniques help drivers stabilise oxygen delivery to their muscles."

Cortisol rises to sharpen alertness and mobilise energy reserves, priming the body for rapid reactions.

160 milliseconds. Reactions so fast it's like you're on autopilot.

Usain Bolt's reaction time in the men's 100m final at the 2008 Beijing Olympics was 0.165s. Fernando's reaction time at a race start is on average 0.16s. A hummingbird's wings will have flapped just 11 times in the time it takes Fernando to hit the throttle when the lights go out. And a fighter pilot's reaction time is in a similar region: 150-250 milliseconds depending on stimulus complexity, such as radar, threat alerts and cockpit instruments.

DOC: "Reaction time is paramount. Drivers usually process visual information in around 200 milliseconds – faster than most athletes. Their brains operate in a 'hyper-alert' state, with neurons firing rapidly to coordinate eyes, hands, and feet.

"Cortisol, another stress hormone, rises to sharpen alertness and mobilise energy reserves, helping to prime the body for rapid reactions."

BULLET: "At the start of the race, it's almost like you're driving on instinct and letting your cerebellum automatically offer solutions to the action around you. Everything's moving so fast that you don't have time to consciously think."

The cognitive capabilities of a chess grandmaster.

A study by University College London, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, found that structural alterations of the brain and differences in the wiring of the right hemisphere of the brain in RAF Tornado fighter pilots meant they were able to execute 'optimal cognitive control' and perform certain tasks more accurately. It's not clear whether pilots are born like that or develop the differences as a result of their training.

In the study, Professor Masud Husain described how fighter pilots are 'often operating at the limits of human cognitive capability – they are an expert group making precision choices at high speed.' The same can be said of F1 drivers making split-second decisions while processing a flood of visual and auditory information in real-time and under extreme pressure.

BULLET: "You need huge cognitive ability to execute a race well."

DOC: "Definitely. Mental endurance is just as important as physical strength."

BULLET: "You need to think about the tyres, the strategy, and at any moment be ready for a coherent conversation with your engineer on the radio."

DOC: "The brain must process huge amounts of information: car data, track conditions, rivals' positions, all while making split-second decisions.

"Drivers use techniques such as mindfulness, controlled breathing, and visualisation to stay calm under pressure. Their training includes cognitive tasks under fatigue, so they can maintain concentration even when their bodies are exhausted and heart rates are high."

I was fainting coming into Parc Fermé. I lost three and half kilos in the race from sweating.

3kg of sweat. Keeping cool and hydrated in cockpits exceeding 50°C.

Inside an F1 cockpit, temperatures can soar to 50-60°C. Fighter pilots feel the heat too: bubble canopies expose the cockpit to high radiant heat load. Sunlight raises the air temperature and heats exposed skin and clothing. But once airborne, altitude, environmental cooling systems and cooling vests offer some relief.

Despite being able to wear cooling vests in the build-up to the race, drivers aren't afforded such luxuries, and even with hydration systems built into their helmets, F1 drivers often finish races two to three per cent dehydrated.

A 1–1.5-litre fluid pouch, often stowed behind the seat or in the nose of the car, feeds into a reinforced tube with a one-way valve that runs up through the cockpit and clips beneath the helmet padding. But unsurprisingly, the liquid, usually a mix of water, electrolytes, and vitamins, can warm quickly in the high temperatures. One press of a thumb-switch on the wheel activates a tiny pump, sending a mouthful of fluid through the valve.

Fighter pilots use a similar system built for altitude and g-force. A hydration bladder is integrated into the flight vest or seat-kit, linked to a flexible hose with a non-return valve that tucks beneath the oxygen mask. It allows a pilot to sip mid-turn without breaking control or risking a spill inside sensitive avionics.

BULLET: "Dehydration is one of the biggest challenges an F1 driver faces.

"I used to tell my engineers to remind me to drink every 10 laps because, when you're in a race, you're not thinking about drinking; you don't even feel thirsty because of adrenaline."

DOC: "It's such a huge challenge for drivers because cockpit temperatures can exceed 50°C; it's common for drivers to lose two to three litres of sweat in a race. The body compensates by diverting blood to the skin to cool down, but this reduces blood supply to working muscles, accelerating fatigue.

"Even two per cent dehydration impairs reaction time, concentration, and decision-making, which is why maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance is critical to sustaining performance over a two-hour race."

BULLET: "There's no warning you're starting to feel dehydrated, you only know when suddenly you feel really unwell. Adrenaline masks the signs of it building up until it's quite serious.

"So, you must find a way to remember to keep drinking. Otherwise, by the end of the race, you'll be feeling dizzy.

"The most difficult race in my career was the 2002 Malaysian Grand Prix. It's always so hot and humid there and my drinks bottle in the car wasn't working.

"I had to count down the last 15 laps in my head one by one, telling myself I would retire after the next lap, just to manage things mentally so I could get to the finish.

"Eventually, I saw the chequered flag, and I was fainting coming into Parc Fermé. I got out the car, stumbled into an empty FIA office nearby and instantly drank a 1.5-litre bottle of water. I felt better fairly soon after that but before then I was feeling very unwell despite being at peak fitness. I lost three and half kilos in that race from sweating."

DOC: "Drivers hydrate aggressively beforehand with fluids containing electrolytes like sodium and potassium to try to avoid this scenario.

"Many also use pre-cooling strategies such as ice vests before getting into the car, which lowers body temperature and delays overheating.

"Heat acclimation training also helps them prepare for high cockpit temperatures."

Blood can pool away from the brain during high g-forces, risking blurred vision or even 'grey-out'.

6.5 g. More than six times the force of gravity.

F1 drivers endure lateral and longitudinal g-force in excess of 6 g in some high-speed corners and under heavy braking. Fighter pilots face vertical g-forces up to 9 g, risking blackout without g-suits and anti-g straining manoeuvres, which help to push blood up toward the brain. Both require exceptional core and neck strength, but the direction and duration of g-forces differ.

BULLET: "Sustained lateral g-force from cornering hundreds of times over a race distance is the toughest force on your body when driving.

"The g-force when braking and accelerating is very impressive, but it is not too difficult to contend with once you build your neck muscles, because you feel them for only a short period of time."

DOC: "When accelerating, forces push the body backwards into the seat.

"At the start of race, acceleration off the line can exceed 2 g, pinning the driver back into the seat. The eyes and inner ear must adapt instantly to the surge, but the brain is trained to filter out these forces so vision remains stable. The neck muscles work to keep the head steady as shearing forces act between the skull and spine.

"Braking can subject drivers to up to 6 g forward. This is equivalent to several times your bodyweight being thrown against your safety harness.

"The driver's muscles, especially the neck, chest, and core, must constantly fight against g-force to keep control of the car and stay focused.

"Such forces can mean the driver's head and helmet, weighing around 7kg in normal conditions, can feel as if they weigh 30-40kg. The neck and shoulder muscles must work constantly to keep the head stable and eyes focused."

BULLET: "It's the lateral g-forces can cause more of an issue. Before I drove the AMR23 at Silverstone Circuit last year, my first time in an F1 car for around a decade, I trained my neck as much as I could to prepare for the lateral forces more than anything else.

"Even so, after a few laps of flying through Luffield, Woodcote, and Copse – all right-handers in quick succession – I had to lean my head on the headrest of the car. The next morning, my neck was very stiff."

DOC: "The semi-reclined posture of the F1 seat does help to distribute these forces more evenly, but it also changes how blood behaves in the body. Blood can pool away from the brain during high g-forces, risking blurred vision or even 'grey-out' if untrained.

"Drivers use core and leg muscle contractions, similar to fighter pilots' anti-g straining manoeuvres, to help maintain blood flow to the brain."

You can start suffering numbness in your toes when you're driving.

100kg through your left foot. Turn and burn in the cockpit.

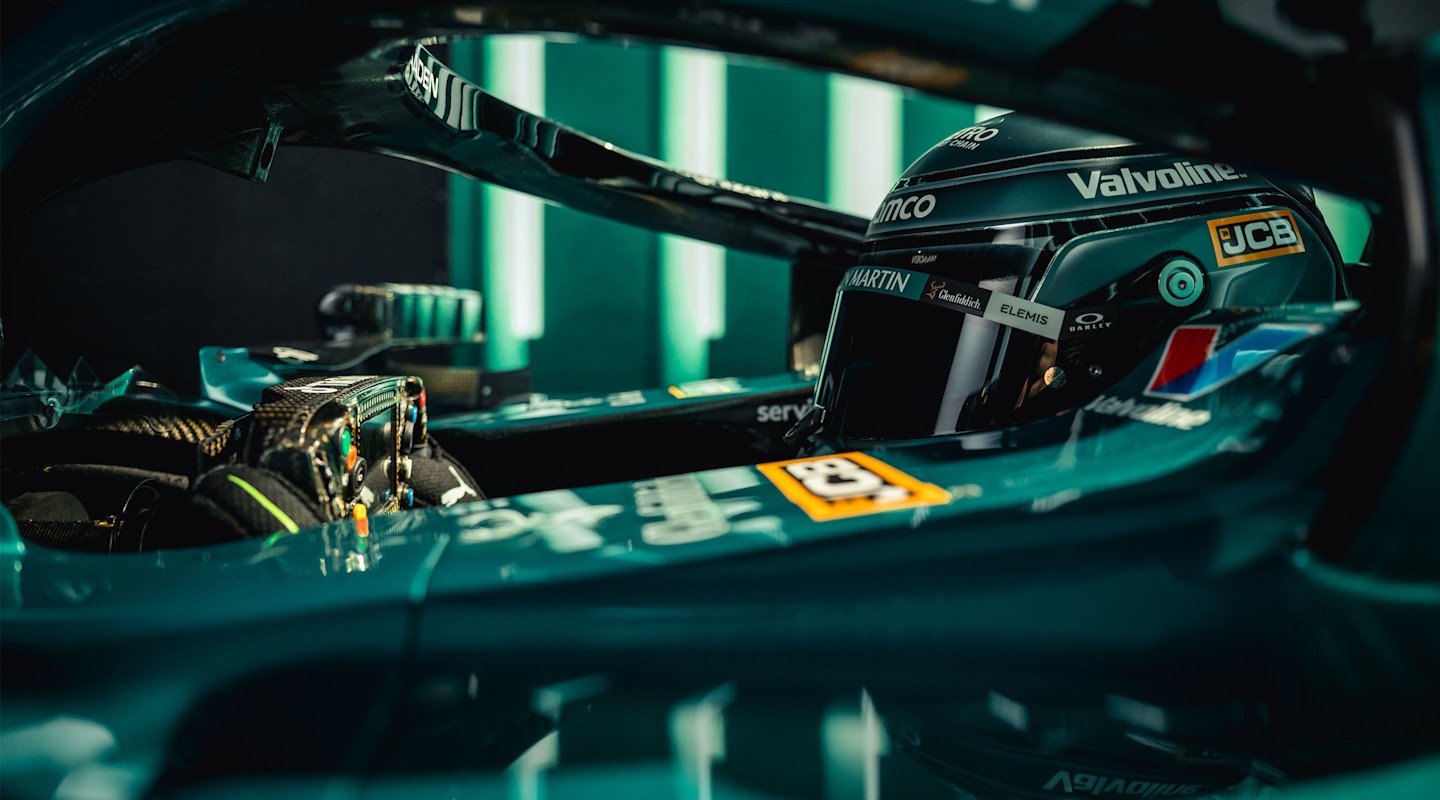

F1 drivers train their necks and cores to resist g-forces and cockpit vibrations. Every lap sends lateral forces through the spine, demanding strength, stability, and endurance just to stay composed in the seat.

Despite extensive conditioning, prolonged strain and constant compression often lead to lower-back pain – the quiet cost of pushing both car and body to their limits.

Fighter pilots face the same enemy on a different axis. Their training builds core, glute and leg muscles to maintain blood flow and posture under 9 g of vertical load. Hours spent strapped into tight cockpits, combined with the weight of flight gear and poor ergonomics, place stress on the spine.

DOC: "Every bump, kerb, and vibration from the track is transmitted up through the car into the driver's spine. Over a race distance, this creates fatigue in the lower back and hips.

"Again, the semi-reclined seat helps spread the load, but the spine and core muscles still absorb a huge amount of energy. That's why core stability training is so important for drivers. It reduces injury risk and helps maintain precision at the wheel, even when the car is bouncing over kerbs."

BULLET: "Dehydration and g-forces are tough on the body, but personally, I found that my lower back suffered the most during a race.

"In the cockpit, you're sitting with your feet level with your chest, and there's so much vibration because the car is low to the ground; you feel every kerb.

"Plus, you're hitting the brakes with around 100kg of force via your left foot, which takes a lot of twisting in your hips."

DOC: "It's equivalent to pressing down with their full bodyweight. This requires powerful contractions from the quadriceps, calves, glutes, and hip stabilisers.

"The hips rotate to brace the pelvis, while the arms and shoulders counter the forward momentum of the torso.

"Each braking event is a battle between the car throwing the driver forward and the driver's muscles and harness holding them in place.

"Over a race distance, a driver will brake hundreds of times, so immense muscular endurance is required to withstand this repeated load without fatigue compromising performance."

BULLET: "It all puts a lot of stress on your lower back, so it's vital to treat it after every race with a massage to stop stress building up, otherwise you can start suffering numbness in your toes when you're driving."

DOC: "The constant cornering and braking lead to lactic acid build-up, causing the 'burn' drivers feel, particularly in the neck, forearms, and legs.

"In addition, despite power steering, an F1 steering system is incredibly heavy compared to a road car. Depending on cornering speed and aerodynamic load, it can take up to 15-20kg of force to make precise inputs. Drivers perform hundreds of steering corrections each lap, making forearm endurance and grip strength crucial.

"Adrenaline helps mask some of this fatigue, allowing drivers to push through, but it cannot completely override physiology."

Related content

Win the race suit

A unique PUMA race suit for a unique livery. A replica of the special-edition United States Grand Prix race suit, signed by Fernando, could have been yours.

Make sure you’re signed up to I / AM to unlock more exclusive giveaways.